Vindication of An American Warning

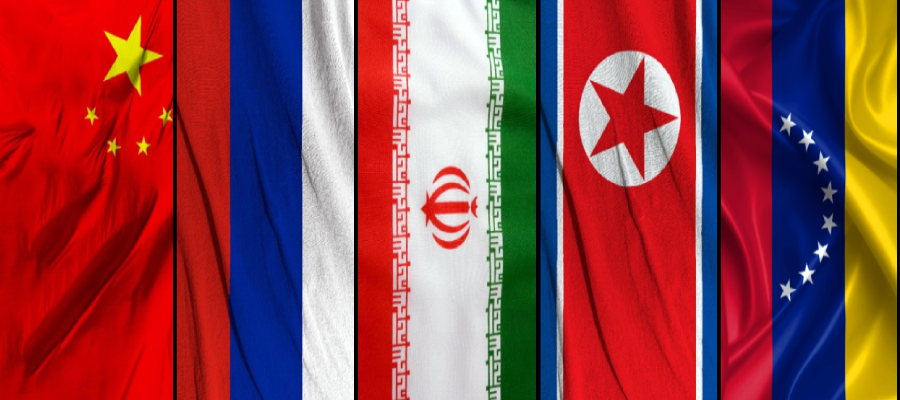

In 2009, I published An American Warning, a poorly written book (I wasn’t the best writer back then—or now) that outlined a forecast of emerging global threats and the dangers they pose to Americans. This was followed up with another book in 2014, Reloaded: An American Warning, which was a stronger warning about how rapidly things were progressing. Among their key analyses was the possibility of a strategic alignment among nations hostile to Western interests. At the time, Russia, China, North Korea, Iran, and Venezuela were loosely associated through some shared ideology and occasional cooperation. However, I emphasized that they would soon become something much bigger in the coming years.

Over a decade later, these alignments are no longer speculative. They have evolved into a tangible geopolitical bloc now informally referred to as the “CRINK” alliance—China, Russia, Iran, and North Korea. In fact, the Wall Street Journal recently wrote an article on the matter titled, “How a New Axis Called CRINK Is Working Against America.“

Now, some might argue that my analysis was a little off because Venezuela was not formally included in that supposed CRINK alliance. I disagree. This situation is still unfolding, and their omission is likely strategic. While Venezuela is not formally included in this acronym (yet), its growing ties with these nations firmly situate it within the orbit of this emerging coalition. Hence, I think a more appropriate acronym would be CRINK-V, or as I called them, “The Big Five” (or maybe “INCRV?”). First of all, I’m not the one in charge of the acronyms, and second, there is a really good chance that the people who came up with “CRINK” are not looking at the same things that I am, let alone why or how this is unfolding.

Understand that this alliance signifies more than opportunistic collaboration; it represents a profound but predictable recalibration of global power structures and a direct challenge to the strategic and economic influence of the United States. Recent developments only demonstrate the urgency of this shift. For example, Russia’s ongoing conflict in Ukraine has drawn material and logistical support from both North Korea and Iran. North Korea has transitioned from being an isolated nuclear threat to becoming an active wartime supplier of soldiers, artillery, and ballistic munitions for Russia. Iran has contributed drone technology and tactical expertise while deepening its commercial and military ties with China. Meanwhile, China continues to act as a lifeline for Russia by purchasing energy resources and facilitating trade that undermines Western sanctions. Moreover, it seems that Chinese soldiers are starting to pop up on the front lines of the conflict in Ukraine. The overlap is real and progressing—in rapid time!

So, what about Venezuela? While its role in the CRINK-V alignment is less overt than that of its counterparts, it is no less significant—and increasingly strategic. Caracas has long maintained deepening relationships with Moscow and Tehran, grounded in military cooperation, energy exports, and a shared anti-Western posture. Notably, Venezuela has supplied crude oil through covert maritime operations that evade sanctions, including shipments linked to North Korea. Investigations have revealed the use of deceptive shipping practices such as identity laundering and ship-to-ship transfers—tactics often employed to obscure the cargo’s final destination. In this shadow network, it is highly plausible that some of this oil ultimately reaches China or other CRINK-V states, reinforcing their ability to sidestep Western containment measures (interesting article here).

Moreover, Nicolás Maduro’s regime increasingly relies on these alliances to navigate crippling economic sanctions and international isolation. Russian advisors have operated on Venezuelan soil, providing military expertise and equipment under agreements that extend through 2030 and beyond. Iranian oil shipments have bolstered Venezuela’s crumbling energy sector. China remains one of Venezuela’s largest creditors, investing heavily in infrastructure projects (that often look like military projects) that secure its foothold in critical sectors like energy and transportation. And the list goes on. And, of course, China and Russia would prefer these initiatives to be less overt.

Militarily, Venezuela has taken steps to reinforce its position within this network. The Bolivarian Shield 2025 military exercises mobilized 150,000 personnel alongside naval, aerial, and armored assets in a display of national defense readiness. These drills essentially demonstrated Venezuela’s intent to project strength domestically while signaling its alignment with broader anti-Western strategies. Moreover, Venezuela has engaged in intelligence-sharing agreements with Russia that include counterespionage initiatives. And the list goes on. So, yes, Caracas is integrated into the strategic objectives of the CRINK bloc, whether anyone wants to admit it or not. At the very least, we should consider them the “silent partner,” with silence being their key advantage.

More than that, we have to consider the location of this “silent partner.” The distance from Venezuela to Florida is roughly equivalent to the distance between Miami and Denver. It strikes me as an ideal location for a strategically adept alliance to establish a foothold, gather intelligence, stage necessary assets, and train in preparation for long-term operations against their collective adversary. Of course, if you review the intelligence longitudinally and holistically, that seems to be exactly what is happening. Yet, the threat may be far closer than any of us would care to imagine.

Immigration from North Korea, China, Iran, and Russia to the United States is a well-documented reality, raising concerns among officials about potential security risks, especially given the vulnerabilities of the U.S. border. However, Venezuelan immigrants should be included in this risk assessment because they represent a significant and rapidly growing demographic within the United States, with an estimated 592% increase over the past two decades. Of course, the part that is often not discussed is the fact that this influx includes thousands tied to organized crime—most notably the Tren de Aragua (TdA), a violent transnational cartel now reported to be operating in at least 22 U.S. states.

Unfortunately, when people hear the word “cartel,” they usually think about drugs and human trafficking. In this case, it’s much more. In fact, this expansion has raised serious security concerns among Border Patrol and Homeland Security agents, particularly regarding the TdA’s alleged connections with Hezbollah, Iran’s proxy group in the Middle East. These concerns are not without foundation. For more than twenty years, Venezuela has maintained a close alliance with Iran and has served as a regional base for Hezbollah’s operations in Latin America. This geopolitical partnership has laid the groundwork for more complex threats that most Americans are oblivious to.

Alejandro Cassaglia, a terrorism and organized crime expert and professor at the University of Buenos Aires, notes that groups like Hezbollah and the TdA are not limited to traditional criminal activity; they are also engaged in hybrid warfare, cyber-intelligence, and terrorism. This makes them particularly important and valuable to the others in the CRINK-V alliance. Supporting this, Jorge Serrano—a security advisor to Peru’s Congressional Intelligence Commission—claims that Tren de Aragua receives direct support from Iran and has forged strategic alliances with Russia, China, and North Korea. These assertions likely contributed to the state of Texas formally designating Tren de Aragua as a foreign terrorist organization. The story goes on, but hopefully, you’re starting to see that the “Venezuelan connection” is a much bigger story than the mainstream narrative would like to convey.

The Implications are Real

On the whole, the implications are far-reaching. This coalition represents not only a multipolar resistance to U.S. hegemony but also a coordinated effort to establish parallel systems that challenge Western dominance. These nations are actively sharing military technologies, pooling economic resources, coordinating diplomatic strategies, and engaging in intelligence collaboration. Of course, the threat posed by this alignment is structural rather than rhetorical; it seeks to erode U.S. influence across regions traditionally under Western stewardship. Not only does this threaten U.S. security, but this will have a profound impact on the dollar, which will definitely impact alliance alignment.

Meanwhile, the effectiveness of traditional U.S. containment strategies is increasingly called into question. Sanctions lose their potency when targeted nations can rely on alternative networks for survival. That’s the point! Diplomatic isolation becomes meaningless when adversaries create their own spheres of influence. The question then becomes, how does a nation impose its will if sanctions are meaningless? Also interesting is that the CRINK-V configuration operates without centralized command structures but thrives on mutual reinforcement. This means that finding the Achilles Heel becomes almost impossible.

As expected, the West’s response has been largely reactive, but it is further hindered by bureaucratic inertia and short-term calculations. In contrast, CRINK-V nations are playing a long game: investing in asymmetric warfare capabilities, cyber operations, proxy conflicts, and infiltration of international institutions that often go unnoticed. What Americans need to understand is that the unity of CRINK-V is not born out of friendship but sustained by shared objectives—the diminishment of American global leadership. Unfortunately, the United States is now filled with citizens who sympathize with that desire, and the rest are seemingly divided, without vision, and have a very hard time trying to wrap their heads around such complexities. By the way, this should provide every patriot with enough motivation to scrutinize the divisive messaging flooding their social media feeds.

Nonetheless, as this alliance solidifies, the United States faces an urgent need to reassess its foreign policy strategies. Deterrence must evolve into proactive engagement supported by long-term strategic foresight, which, admittedly, will be a challenge because the United States has been conditioned to reactivity and instant gratification untethered to vision or outcome. Either way, I think American alliances should be deepened based on shared outcomes rather than mere military presence (which requires actually having a vision). Economic independence from adversarial states must be prioritized alongside investments in technological innovation domestically, especially to counter non-traditional forms of warfare.

The point is that the warnings I outlined over a decade ago are no longer theoretical—they are unfolding realities. I was accurate about several things, and I fear that I’m accurate about the others, as well. The age of ambiguity has ended; decisive action is required if the United States hopes to maintain its role as a global leader. But therein lies another question: What about the other warnings, and what can we expect moving forward?

My Projection Model

If current trajectories persist and the CRINK-V alignment deepens alongside an expanding and emboldened BRICS consortium, I would say that the coming years are likely to witness a fundamental realignment of global power structures that will significantly challenge Western influence. This is to say that if the United States does not get its act together, at the very least, one can reasonably expect the emergence of a dual-order world in which parallel institutions, currencies, and trade systems reduce the hegemony of U.S.-led frameworks.

Let’s just consider the strengthening of BRICS. It seems that many have all but forgotten that this is unfolding in real time. With new member states such as Saudi Arabia, Egypt, and others exploring accession, there seems to be a growing appetite among nations for alternative economic alliances that are less dependent on Western inflationary nonsense. Should BRICS succeed in establishing a viable commodity-backed currency or a widespread alternative to SWIFT, I think that there is a strong possibility that the United States could face a diminishing ability to leverage the dollar as a geopolitical tool in the very near future. Of course, in a lot of ways, that is already happening. When you factor in things like China’s Cross-Border Interbank Payment System (CIPS), the petro-yuan, or BRICS digital currency, it’s easy to see what they’re shooting for and where this is going.

On that note, I think it might be wise for people to re-think what Trump might really be doing with these tariffs. Some seem to think that these tariffs are fueling a dollar exodus. I can see that argument, but I think it might be flawed. The desire to leave the dollar started long ago.

Now, I could be wrong, but I tend to believe that these tariffs, especially when levied on high-value imports or critical sectors, directly impede these nations’ growth trajectories by limiting access to Western markets, suppressing export revenues, and triggering retaliatory trade policies that isolate them from broader economic participation. In effect, I think these tariffs are acting as tools of containment—choking off economic oxygen from key players seeking to challenge the Western-led global order (the dollar). That’s why some nations have been so quick to come to the negotiation table.

Of course, I’ve yet to see a serious discussion acknowledge this reality. Instead, most coverage frames the BRICS realignment as a reaction to current tariffs—when, in truth, BRICS has been quietly growing since at least 2010. In fact, between 2022 and 2023, the bloc made its most coordinated and strategic leap forward. Not so coincidentally, that was also around the time the U.S. began promoting a revised definition of “recession.” Funny how that works.

The point isn’t partisan—it’s structural. It’s not Trump’s fault; it’s the dollar’s. Dependence on the U.S. dollar has forced many nations to import inflation and accumulate unsustainable levels of dollar-denominated debt. No one likes that. Of course, they want out—and really, can you blame them? You’re probably just as tired of inflated prices here at home.

But here’s the part most people miss: aggressive tariff regimes are more likely to hinder BRICS momentum than accelerate it. China’s export-driven economy is especially vulnerable in sectors like semiconductors, green technology, and telecommunications. Russia, meanwhile, is increasingly dependent on China and BRICS-aligned trade to counterbalance Western sanctions. But its ability to fund geopolitical ambitions—whether in Ukraine or through energy diplomacy in the Global South—is constrained when tariff walls fracture global markets.

Meanwhile, Iran, North Korea, and Venezuela—already sanctioned and isolated—depend on economic cooperation with BRICS and other non-aligned nations to survive and resist Western hegemony. U.S. tariffs that disrupt BRICS cohesion or reduce China’s and Russia’s capacity to support these rogue states indirectly extend American leverage, curtail the spread of anti-Western coalitions, and delay the emergence of any viable global counter-system. How is this missed by so many? Moreover, why are so many American “allies” missing this? All this to say that while tariffs are framed in economic terms, I think their true impact lies in their capacity to fracture geopolitical alliances and stall the momentum of revisionist powers. And if that was not the intent, then it is a very lucky happenstance. Of course, most Americans are not thinking in these terms because anti-American media (and social media via 5GW) has done a fantastic job of confusing and angering the ignorant. I’ll discuss this in a moment.

Side Note: The Carnegie Endowment for International Peace wrote an interesting piece called “BRICS Expansion and the Future of World Order: Perspectives from Member States, Partners, and Aspirants.” It gives some pretty interesting insights from the BRICS perspective. Link Here

Understand that if the CRINK-V situation isn’t fixed, then militarily, they could very well evolve into a de facto security alliance, coordinating even more joint exercises, technological exchanges, and proxy engagements that mirror but deliberately counterbalance NATO operations. “Counter” is the keyword, and we are already seeing hints of it. However, if that happens on a larger scale, then diplomatically, these nations would increasingly dominate or obstruct consensus in the UN, the WTO, or the IMF—which, of course, help Russia and China gain a stronger foothold while simultaneously crippling what is left of the dollar. In this scenario, strategic isolation of Western allies, growing instability in contested regions (like the South China Sea, Baltics, and the Middle East), and the erosion of U.S. deterrence capabilities would not be isolated outcomes. In fact, they would literally become systemic shifts that define the future of global competition, one where America is no longer the uncontested center of gravity.

Probabilities

Now, there are plenty of people who would like to argue that the likelihood of global war in the near future remains constrained by structural deterrents like nuclear weapons and economic interdependence. That’s not a bad argument, but I think that misses the point. Furthermore, I think that position ignores historical war cycles and contemporary power shifts. I also think that position is rooted more in cognitive dissonance than reality.

I have written about this many times and in many ways (like here – and here), and I have even produced a video on the matter, but from a historical-cyclical perspective, the convergence of geopolitical realignment, economic instability, technological upheaval, and ideological polarization suggests that the world is rapidly approaching an inflection point (ref: The Fourth Turning by Strauss and Howe, Kondratiev waves, or even Toynbee’s theories of civilizational rise and fall). Granted, strategic forecasting does not deal with certainty. It’s about probability. Nonetheless, and from what I’ve described, it seems that there are several signals that suggest that the conditions for a large-scale conflict are emerging, even if not yet fully triggered.

First of all, we are overdue for a major conflict. War cycles averaged 50-60 years, with the last major systemic conflict (WWII) occurring about 80 years ago. Therein lies our first clue. Current tensions align with characteristics of late-cycle dynamics: shortening conflict intervals (now 7-10 years between major crises), exponential growth in military casualties (+300% since 2000), and consolidation of power blocs. At face value, that’s a fairly strong case, but then there are the “risk multipliers” to consider.

We could look at this a number of ways, but I think we should probably start with power transition theory. This sets the stage for much of what should be explored. According to the Congressional Budget Office, and largely due to weak population gains (divergence from family values), technology, and increased government spending, the United States is expected to see slower overall economic “growth” over the next 30 years. That’s likely why immigration seems so appealing to the power structure. Regardless, some economic data suggests that US GDP (currently at 24.8%) may not just slow but actually begin to reverse. That makes the United States the declining incumbent. Conversely, and contrary to popular belief (or opinion), China’s GDP is growing, making it a rising challenger, now with 18.6% of global GDP. This is to say that there is a good chance that China can or will match or even overtake the U.S. in the not-too-distant future. Well, history suggests that at least 70% of such transitions since 1500 resulted in major war.

Now, before I move on, I should revisit the tariff/BRICS situation. Hopefully, what I have shared with you will help open your mind to other possibilities about what is really going on. At the same time, it should open your mind to why opposing narratives are being pushed so hard. Remember that propaganda and astroturfing are very real and constant.

Now, I look at the CRINK-V coordination as one of the strongest indicators. As demonstrated, their alliance and cooperation have deepened, with shared military technologies and sanctions-evasion networks. That, in and of itself, is big, but not the point. The issue is that this network handles at least $387B in annual trade, and that is growing year-over-year. There is little doubt that this would be protected, and there is little doubt that the Western powers and banks hate this—largely because it hurts the staying power of the dollar. Hence, conflict. I see this as creating a slew of tripwire scenarios where regional conflicts (e.g., Iran-Israel, Baltics, etc.) could rapidly globalize through alliance commitments.

But above and beyond all that, I see the Adversity Nexus and Epistemic Rigidity playing a central part in all of this. The world hasn’t changed much since WWII. That, in and of itself, is probably enough because it is representative of stagnation, and adversity typically follows. However, instead of changing our trajectory toward growth, we seem to be doubling down on status quo nonsense due to the rigidity. I’m sorry to say, but the outcome is highly predictable. But it’s not like we don’t already have the red flags.

In fact, I would argue that the entire global system now shows strong and similar hallmarks of pre-collapse rigidity—the very same hallmarks that we saw in 1914 and 1939. Think about it. There has been at least an 85% reduction in neutral states since 1991, and roughly 60% of UN member states now align with major blocs, all while seeing a 40-year high in military spending ($2.4T in 2023). You really don’t need strategic forecasting capabilities to see where this goes because even a rough appreciation for cause and effect tells the tale.

Of course, I would also argue that war cycle timing, power transition stresses, and alliance dynamics have created the most dangerous geopolitical environment since 1945. Now, that doesn’t mean that a kinetic war is inevitable. After all, the deterrence mechanisms previously discussed are there, and I concede to that. However, less likely does not equate to impossibility, and it’s not like a slew of proxy wars are not already underway. Then, you can add the instigators and antagonists that we invited to our country without so much as a simple screening. Any of these situations could easily tip over into direct conflict between larger powers or cause massive disruptions and chaos at home.

Of course, the economic situation alone could be enough. If the economic situation continues its decline, and the dollar continues to weaken, we probably shouldn’t rule out a collapse or a very large fall from our current status. Of course, either of those could, and likely would, lead to some kind of a civil war, and I think we are already well-positioned for that.

Regardless, what I want you to see here is that it is not just war with an outside threat that we have to think about. However, all of this seems to be pushing us in that direction, so it is probably not a bad idea to keep that in the back of your mind. Of course, all of this might be why The Global Risks Report 2025 identifies state-based armed conflict as the #1 threat. According to the IMF, some 23% of experts rated it the most likely material crisis. Frankly, I am actually a little surprised those numbers are not higher, especially when you consider what I’m about to share with you.

Here is Something Else to Consider

Indeed, many are worried about the global conflict on the horizon. As demonstrated, that is a valid concern, and the risks are rising. However, some argue that the war has already begun. For example, analyst Joseph Epstein wrote an article for Newsweek in 2023 titled “We’re Not on the ‘Brink’ of WWIII. We’re in It.” In 2024, Vladimir Solovyov, a state TV host on the Russia-1 channel, said, “You want WWIII? You are already in it!” In fact, Moneywise recently reported that Jamie Dimon, CEO of JPMorgan Chase, told a crowd that “World War III has already begun.” These are just three of what seem to be endless examples.

So, what’s really going on? Why are so many convinced that it has already begun? Sure, there are kinetic conflicts that are starting to spring up, and those are likely to increase in number in the coming years. But I think it is more than that.

We often overlook the fact that world governments now possess advanced technologies that have fundamentally transformed the nature of warfare. The way wars are fought today has already shifted dramatically from the strategies and tactics of the past. World War III, if it unfolds, will not resemble World War II in any meaningful way. Considering the capabilities of these new technologies, it becomes increasingly plausible that a global conflict is already underway—albeit in a form that is less overt. This conflict may be obscured by the amorphous and decentralized nature of fifth-generation warfare (5GW), which relies on psychological, informational, and cyber tactics rather than traditional military engagements.

Side Note: I did a video on 5GW a while back – CLICK HERE if you’re interested.

If you examine everything through the lens of non-kinetic, systemic destabilization tactics, there is a very strong case for the idea that it has already begun. It’s not just “Ideological subversion” and “Active Measure” tactics, either. On a weekly basis, you can find a new article or video about cyberattacks, disinformation campaigns, economic coercion, and societal divisions instigated by state actors without formal declarations of hostility.

The 2016 Colonial Pipeline cyberattack, Russia’s interference in elections, and even TikTok’s brain-rot initiatives are a few great examples. These operations are very real, but they occur in a supposed “gray zone” where aggression (and susceptibility) is often deniable, borders are irrelevant, and the lines between war, peace, freedom, and indoctrination dissolve. Just consider the previous Tren de Aragua example. CRINK-V can all deny involvement when the TdA engages in cyber-intelligence gathering operations. After all, the decentralized nature of non-state actors using sophisticated technologies in innovative ways is easy to dismiss. But the question probably isn’t who did it; it’s who ended up with the intel and how much it cost.

And if you think I’m exaggerating about platforms like TikTok, then consider that TikTok has already been identified as an exceptional tool for 5GW and psyops due to its ability to manipulate information environments, disseminate propaganda, and influence public opinion at scale. It’s also an astroturfer’s dream come true. Its algorithm tailors content to individual users, making it a highly effective platform for targeted messaging and disinformation campaigns. In fact, numerous investigations have demonstrated its use in spreading propaganda, and concerns have repeatedly been raised about its parent company’s (ByteDance) potential involvement in surveillance and influence operations on behalf of the Chinese Communist Party. I’m picking on TikTok, but that’s just one example of many. The same operations can happen on any social media platform. Consider it “Digital Colonization” or, at the very least, infiltration.

The warning is simple: Be mindful of the narratives you choose to believe—it could be 5GW trying to get you to support things that are not in your best interests. On that note, it could easily be argued that 5GW tactics are significantly more dangerous than flying bullets, largely because they leave entire societies confused, ignorant, divided, and in a perpetual state of vulnerability. As previously discussed, vulnerability typically fosters reactive thinking, which keeps us on our heels and prone to miscalculations. Factor in the ignorance, confusion, and divisions, and missteps are likely. However, it only takes one significant misstep to achieve kinetic activity on either a domestic or global front. This is a big deal.

Indeed, I could go on, but you probably get the point. I guess the only thing left to say is that strategic foresight is only valuable if it is matched by strategic resolve. However, that resolve must always be based on a solid vision (destination)—a vision that the people of this nation have seemingly forgotten about (cohesion and constitutionalism). Perhaps I’ll write an article about it in the coming weeks. Nonetheless, the clock has moved forward, and the world is catching up to what so many refused to see years ago. What happens next will depend not on how comfortable the West remains in its contorted narratives or its dying dollar but on how willing it is to appeal to accuracy, adapt, unify, and prepare for the long game—a game its rivals started playing a very long time ago.